Bolsonaro’s Presidency, REVISITED

Five years ago, Brazil elected the first army officer to power since the end of the military dictatorship. We assess his presidential term.

November 24, 2024

Brazil is the 5th largest country and the 8th largest economy in the world.

It is the largest country in South America, making up around half of its territory, economy and population size. t shares a border with almost every other country in South America.

Brazil is politically free and is the 4th largest democracy in the world.

Brazil is a federal republic with a presidential system of government. This means the regions have significant authority in local laws, while the President is more influential than the parliament on national laws.

Brazil gained independence from Portugal in 1822 without war and kept a monarchy which was replaced by a republican government in 1889.

1964 – 1985: a military dictatorship ruled Brazil. The current democratic constitution was passed in 1988.

Bolsonaro was the first president of Brazil with a military background since the end of the dictatorship.

Brazil is among the world’s biggest players on commodity and resource markets.

It holds the world’s 3rd largest rare earth reserves.

Brazil is the 2nd largest producer of iron ore and 4th largest of aluminium ore.

It also holds significant reserves of uranium and lithium.

It is the world’s largest exporter of beef, chicken, soybeans, sugar, coffee and corn making it very influential in global food trade.

Brazil is the world’s top exporter of cotton, crucial for clothes manufacturing.

Brazil produces enough crude oil to meet domestic demand and still export around 1.7 million barrels a day, equivalent to $119 million at current prices.

Its key export and import partners are China and the USA, accounting for 26% and 11% of exports, and 24% and 18% of imports.

Brazil is the strongest military in the region and produces its own weapons, aircraft, armoured vehicles, missiles and drones.

It is often involved in operations against criminal groups, in particular drug gangs. Brazil spends over $10 billion a year fighting such groups.

Jair Bolsonaro attended Brazil’s top military schools after which he spent 17 years in the army. Bolsonaro would repeatedly praise the era of military rule and call for its return after leaving the army in 1988.

In 1989, Bolsonaro won a seat on the Rio de Janeiro city council. Two years later he was elected to represent Rio de Janeiro state in the parliament. He would hold this 4-year position for 7 consecutive terms.

Like other Brazilian politicians, Bolsonaro often changed his political party.

Having entered office as a member of the Christian Democratic Party, he would change party 7 more times.

In 2018, Bolsonaro decided to run in the presidential election in response to several factors.

Long and severe recession that coincided with the second presidential term of Dilma Rousseff of the Workers’ Party.

Corruption scandal which linked the national oil company and several high-profile politicians including Rousseff herself and her predecessor Lula, who is currently the president of Brazil since 2023.

Election of Trump in 2016 signalled an opening for anti-establishment politics.

Bolsonaro positioned himself as an anti-establishment candidate. This was reflected in his communication style, which refused to respect the conventions of political correctness, and strategy, in which he made heavy use of social media.

He campaigned on the promises of:

Law and order against violent crime and corruption via tougher sentencing and looser gun laws

Economic liberalisation including pension reform aimed at reducing the state’s involvement in the economy

Reducing the national debt

Cultural conservatism on social issues

During pre-election campaigning, Bolsonaro survived an assassination attempt which required life-saving surgery.

Despite staying in a hospital bed and then at home, he would win the first round of the presidential election with 46% of the vote and the second with 55%.

Bolsonaro appointed a Brazilian investor Paulo Guedes as the minister for the economy. This was a new ‘super-ministry’ which combined the previous ministries of planning, finance and industry with the goal of wide-reaching economic reforms.

Guedes has a PhD in economics from the University of Chicago and was popular amongst international investors.

In 2022, Bolsonaro would narrowly lose to Lula, the former president whose conviction for corruption had been overturned by the Supreme Court. Bolsonaro repeatedly claimed there had been widespread electoral fraud, refused to concede defeat and did not attend Lula’s swearing-in ceremony.

Coup – a sudden use of political force to take over the government’s power

A week after Lula’s inauguration, several thousand of Bolsonaro’s supporters stormed the Supreme Court, the National Congress Palace and the Presidential Palace with the aim of making a coup and restoring Bolsonaro.

In June 2023, Brazil’s Supreme Court voted to ban Bolsonaro from running for president until 2030.

In November 2024, Bolsonaro and 36 others were charged by the Brazilian police of attempting a coup.

COVID-19

One of Bolsonaro’s promises was to eliminate the budget deficit in his first year and achieve a surplus in the second. He therefore resisted calls to shut down economic activity in response to COVID-19.

He fired two Health Ministers between April and May 2020 following disagreements over social distancing and the efficacy of eventually unproven medications.

The federal government implemented no nationwide lockdown or social-distancing measures throughout the entire pandemic.

As a result, the response was led by the local governments who instituted lockdowns and social-distancing to curb the spread of the virus.

Despite repeated criticism by Bolsonaro, the Supreme Court ruled in April that state and municipal governments had the authority to adopt such measures.

The federal government’s response centred instead around economic measures to support the economy.

Between 2020 and 2022, the support totalled $115 billion. The bulk of support went to the following initiatives:

Direct transfers to the unemployed, self-employed as well as informal workers and those in extreme poverty. This totalled $62 billion over three years.

Emergency funds, primarily for the Ministry of Health, which totalled $13.5 billion.

Financial support for Brazil’s subnational states and municipalities, which reached $13.5 billion.

Guarantees to credit providers, equivalent to $10 billion.

Income support to formal workers whose employers chose to reduce their working hours or suspend their contracts. This reached $7 billion in total.

The federal government also led the purchase and roll-out of vaccines.

After firing his second Health Minister in May, Bolsonaro appointed an army general to the role.

This appointee repeatedly promoted ineffective anti-malarial drugs like chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine.

Brazil missed the opportunity to source 70 million doses from Pfizer and saw its plan to manufacture AstraZeneca’s vaccine domestically repeatedly delayed, despite having state-funded production facilities able to manufacture vaccines at scale.

Consequently, Brazil’s vaccine programme began in mid-January 2021, several weeks after its neighbours and relied at first on China’s Sinovac solution.

During Bolsonaro’s presidency, a parliamentary investigation was launched into his handling of the pandemic.

The senate approved the report which recommended Bolsonaro be charged with ‘crimes against humanity’, the crime of ‘epidemic resulting in death’ and misuse of public funds for his role in the pandemic. Ultimately, the Prosecutor General chose not to press charges.

Bolsonaro was vocal in criticising:

Lockdown measures

Social-distancing and self-isolation

Mask-wearing

Vaccination

Overall, Brazil had the highest levels of COVID spending in the region alongside Argentina and Uruguay.

Brazil’s excess deaths per 100,000 people were among the worst 25% globally, and higher than neighbours with lower levels of spending like Chile, Colombia and Paraguay.

Out of similarly high-spending countries, Argentina had an even higher mortality rate, while Uruguay’s was significantly lower.

A key piece of Bolsonaro’s political vision was economic reform, specifically liberalisation, deregulation and privatisation.

As in other countries, the ultimate goal of deregulation was to reduce the involvement of the Brazilian state in the economy, aiming to (1) reduce public debt and (2) stimulate private business activity.

Bolsonaro successfully implemented a range of economic reforms.

Economic liberalisation

Changes to business law

Removal of the requirement for public licences for low-risk economic activity

Equalling digital documents to physical documents for all legal purposes

Private sector involvement

Simplified the opening and closing of companies and standardised the payment of international trade fees

Established a more favourable legal framework for startups, including tax incentives and new investment mechanisms

Pension reform

Raising the retirement age from 56 to 65 for men and from 53 to 62 for women over the course of twelve to fourteen years.

Pension spending accounted for 44% of the federal budget in 2018 or 8.6% of GDP.

Crucially, this figure would have risen to 17% of GDP over the next four decades without any reform. Therefore, the total savings were estimated at $169 billion.

Bolsonaro was the first president to achieve pension reform in thirty years.

This is because pension reform required a change to the constitution and therefore approval of two thirds of Congress was necessary. An attempt by the previous president had failed by one vote.

Privatisation in the energy sector

Bolsonaro created Brazil’s first wholesale gas market, which opened the industry previously dominated by the state-owned energy giant

Bolsonaro also permitted greater foreign ownership of Eletrobras, the country’s largest utility company, where he reduced public ownership from 72% to 45%.

Bolsonaro’s promise throughout his election campaign was tackling crime in Brazilian society, both violent crime and corruption.

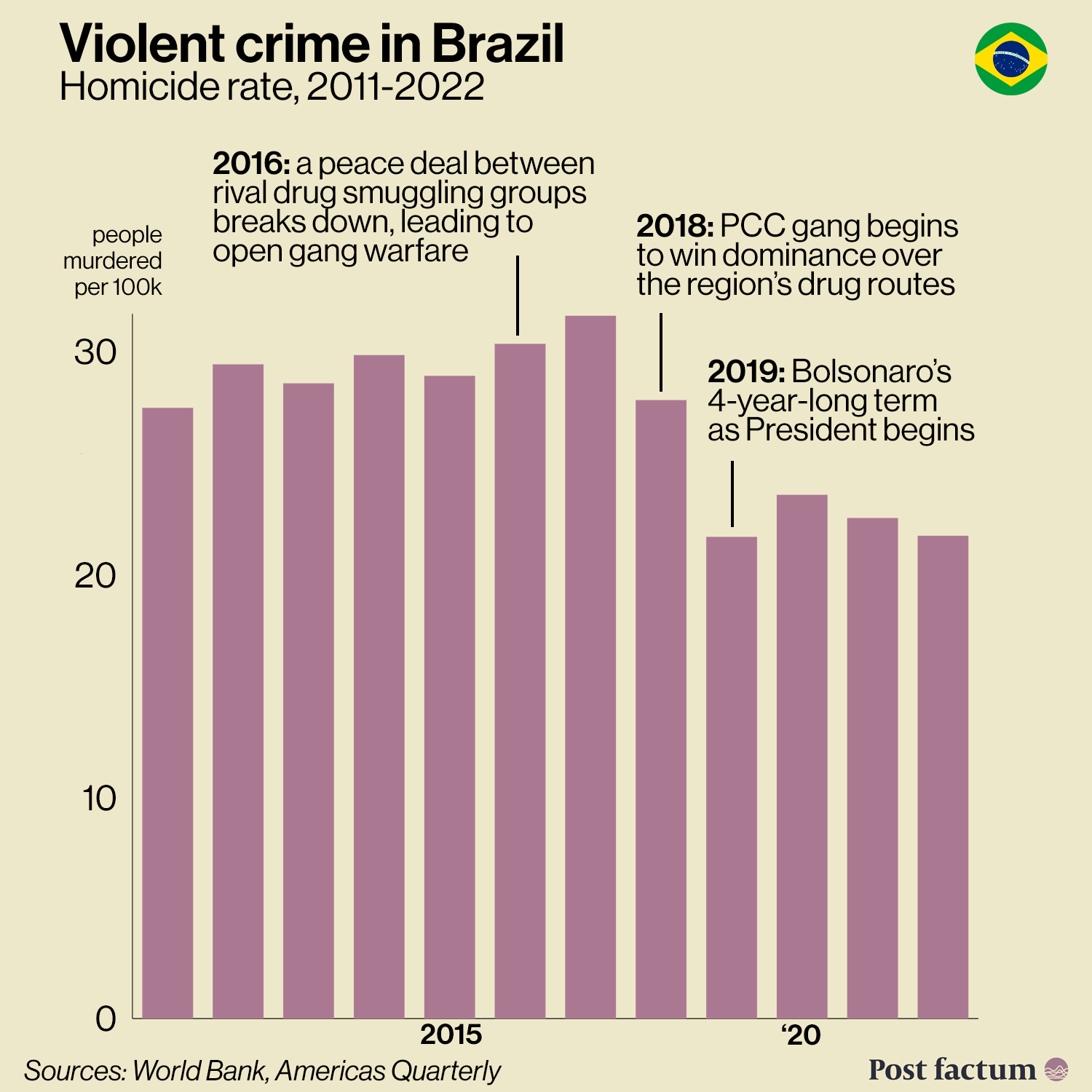

Brazil’s murder rate had previously increased by 50% between 1990 and 2017. A particular spike of violence started in 2016 when a gang war broke out.

Bolsonaro’s reforms approached the problem from different angles. One of his earliest promises involved loosening gun laws and throughout his presidency he made more than 32 changes to this effect.

ability to buy more powerful weapons

looser restrictions on ammunition

Between 2018 and 2022, the number of guns in private hands doubled to nearly 2 million.

It is notable that the national homicide rate started to fall dramatically from 2018.

Although supporters of Bolsonaro point to his policies as responsible, others point to the cooling of conflict between the two main drug trafficking gangs as the turning point.

Bolsonaro promoted deforestation in the Amazon. He removed powers from state agencies tasked with fighting deforestation and cut environmental funding, in pursuit of deregulation and ease of business.

Under his rule, deforestation increased by 75%, reaching a 15-year high.

Bolsonaro aggressively dismissed environmental concerns and even financial aid to fight forest fires.

Some of the reasons for pursuing pro-deforestation policies were:

Looking to secure votes from agricultural and industrial workers who don’t want government regulation over land

Support of the agricultural sector’s political lobby

The current president Lula, re-elected in 2023, is trying to reverse these policies and has stopped the growth of the deforestation rate.

He also pursued the reversal of some of Bolsonaro’s gun laws and privatisation plans but is slowed down by having to mobilise support of multiple parties and compromise with the interests of the agribusiness.

Author Julien Machiels

Editor Anton Kutuzov

You can help us secure our long-term future!

Please consider sending us a regular donation.

Find out more: